This post is an installment in our "Meet a Scientist" Series

Last fall, a baby gorilla in Rwanda was named Macibiri by the CEO of the Fossey Fund. Though Rwanda’s annual gorilla naming ceremony occurs each year, last year’s baby gorilla name was special. September 2017 marked the 50th anniversary of the Karisoke Research Center in Rwanda, Africa.

Macibiri was named after Dian Fossy, the primatologist and anthropologist, who established Karisoke and began what is now known as The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International. Little Macibiri is actually the granddaughter of a silverback leader, Titus, Fossey herself studied in the 70s. Her name came from Nyiramacibirim, Fossey’s nickname in the Kinyarwanda language. Fossey advanced gorilla research and conservation forward at a time when it was much needed. Her perseverance and passion led her to be one of the world’s most influential primatologists. Along with Jane Goodall (chimpanzees) and Biruté Galdikas (orangutans), these women together were known as the “Trimates.”

Fossey’s life and work is a study in contradictions. On one hand she paved the way for a better life for generations of gorillas like little Macibiri, promoted conservation, and persevered as a woman during a time people were openly hostile to women in science. On the other hand, her actions towards poachers and other people in Rwanda ranged from unkind to criminal and horrifying. Ultimately her actions may have led to her murder. Learn more about both her life, her work and it’s legacy along with her darker side and actions.

The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International in Rwanda. Photo Courtesy of Azurfrong/Creative Commons.

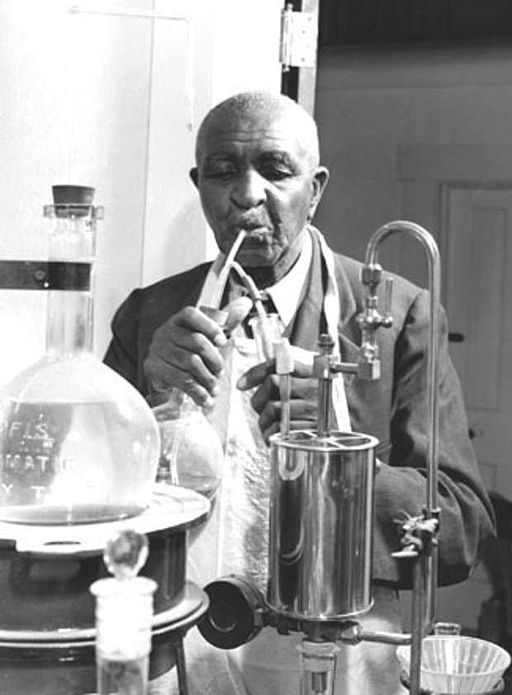

There are no known public domain images of Dian Fossey - but you can see her image here.

Dian Fossey was born in 1932 in San Francisco, California. Though she loved animals from a young age, her path to becoming a primatologist took some twists. She initially followed in her stepfather’s footsteps and studied business at Marin Junior College. After her first year, she spent a summer on a ranch in Montana. This experience led her to switch from business to become a pre-veterinary student at the University of California. However, she switched again and ultimately graduated from San Jose State College with a degree in occupational therapy in 1954. After working with tuberculosis patients in California, Dian moved to Louisville, Kentucky to work as director of the occupational therapy department at Kosair Crippled Children’s Hospital.

It would take almost another 10 years before Dian made her way to Africa.

The Life Changing Decision

Fossey always wanted to travel the world and go to Africa so when a friend returned from there after a vacation with pictures and stories, Dian knew it was her turn to travel. In 1963, she took out a bank loan along with her entire life savings and made her way to Africa. During this first trip, she traveled to Kenya, Tanzania, Congo and Zimbabwe.

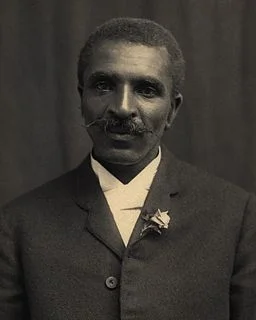

One of her final stops on this excursion was the Olduvai Gorge in Tanzania, where she met Dr. Louise Leakey. He was a famous paleoanthropologist and archaeologist who demonstrated that humans evolved in Africa and promoted primate field research. Just a few years earlier, he supported Jane Goodall and her work with chimpanzees, which was only 3 years old at the time. Meeting Leakey was a major turning point in Fossey’s life. The second was meeting Joan and Alan Root in Uganda, close to the Virunga Mountains. They provided Dian with her first opportunity to witness the beautiful gorillas that would soon inspire her life work.

Dian eventually returned home back to a life as an occupational therapist, but as history now knows, this would not last long. Fossey published several articles and photographs from her Africa travels. A few years later, Leakey came through Louisville on a lecture tour. Dian eagerly spoke to him again after his lecture and left an impression. Leakey proposed Dian consider leading a long-term field project studying gorillas in Africa. Eight months later, he secured funds and in 1966, Dian Fossey headed back to Africa.

The Beginning of a Legacy

As Dian headed back to Africa, Joan and Alan Root once again helped her along the way. She set up camp at Kabara, which lay close to Mt. Mikeno in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. There, she teamed up with an experienced gorilla tracker named Senwekwe who helped her find gorillas. Slowly, Fossey refined her ability to find and interact with gorillas. During this time, she managed to identify six gorilla groups in the area.

Unfortunately, the political situation in the Congo was harsh and in the middle of a civil war. In the summer of 1967, soldiers escorted her away from camp. They kept her in Rumangabo for two weeks until she escaped after bribing guards with cash to help her leave. What happened to her during this time is unclear, but accounts suggest she was abused. The U.S. Embassy warned her not to return but she ignored these warnings. She, with Dr. Leakey’s support, made plans to continue her work at a new site.

September 24, 1967, Dian Fossey established the Karisoke Research Center. 50 years later, this same center would be the home to Macibiri.

Karisoke Research Center

“Kari” – Mt. Karisimbi

“Soke” – Mt. Visoke

Dian set up the Karisoke Research Center in the Volcanoes National Park on the Rwandan side of the Virungas, in between Mt. Karisimbi and Mt. Visoke. Alyette DeMunck, a Belgian woman who was born and lived in the area, helped Dian find the site, communicate with the local people and became a close friend. As Dian began studying the gorillas in the area, she based her methods on those set by George Schaller. He wrote The Mountain Gorilla: Ecology and Behavior in which he highlighted the intelligence and beauty of gorillas. Fossey built off of his methods which involved “habituating” the animals to her presence, allowing her to observe them more closely. Fossey’s habituation process depended on the gorillas’ natural curiosity. She never bribed them to interact. She would “knuckle-walk” and chew celery to draw the animals near. She would mimic their vocalization. Her methods of gaining the gorillas’ trust were only part of her contribution to the field. She completely altered how the public saw gorillas.

Dian’s passion for the gorillas knew no bounds. Soon after she established Karisoke, she bonded with a 5 year old gorilla, aptly named Digit as he had a damaged finger on his right hand. Digit and Dian grew close. Digit was part of one of the groups Dian observed but he did not have playmates his own age. Dian herself was quite isolated and alone in her own studies. Tragically, on December 31, 1977, Digit died protecting his group from poachers.

The threats to mountain gorillas included poachers, environmental encroachment by humans and a lack of public sympathy for the animals, as they were perceived as violent and scary. Digit’s death made Dian realize that she needed to take action and bring attention to the plight of the gorillas. She began the Digit Fund to support “active conservation” and anti-poaching initiatives, which has now evolved into the Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International. Dian wrote several pieces for National Geographic, including one about Digit’s death so that, for the first time, the public could see gorillas as Fossey saw them: as intelligent, social and complex individuals, not the monsters they were often portrayed to be. She shared their names, their personalities and dynamics; she humanized them just as Jane Goodall did with the chimpanzees.

Beyond Karisoke

Dian’s journey to becoming a primatologist was anything but linear. Even after years of field work, it bothered her that she did not have her doctorate. So, in 1970, she enrolled in Darwin College, Cambridge to study under Dr. Robert Hinde, who had also been Goodall’s mentor. Four years later, she walked away with a completed PhD. A few years later, Fossey eventually took time away from Karisoke to act as a visiting associate professor at Cornell University in 1980. She also began working on her manuscript, Gorillas in the Mist chronicling her time spent with mountain gorillas. The book was published in 1983 and a movie with the same title was released in 1988. Both were largely successful; the movie even gained Oscar recognition.

Dian Fossey’s Dark Side

Despite the positive awareness Dian induced, accounts of Fossey’s fight against poachers and efforts in “active conservation” describe aggressive and violent actions. Fossey feared that traditional, and potentially passive, long term goals would be useless and ultimately too late to save the dwindling mountain gorillas.

The death of the gorilla Digit at the hands of poachers led her to essentially declare war with the poachers, an effect with violent ramifications for both herself, the poachers, other locals and the gorillas. She often attacked and even killed the local’s cattle. She burned the homes of those she found guilty, fought and interrogated perpetrators, even bribing park rangers to help her. In the most horrifying story of her actions, she kidnapped the son of a poacher in retaliation for his alleged kidnapping of a baby gorilla. Poachers often targeted and killed gorillas that she was studying.

Though she did have human allies, as the years went on, an increasing number of accounts describe her personality as difficult and quite tortured. After years of largely isolated studies in the wild and a fire for aggressive conservation, many saw her as someone with far more compassion for gorillas than humans. To this day, many still wonder if and how this behavior contributed to her eventual murder.

A Tragic and Mysterious Ending

On December 27, 1985, just a few weeks before her birthday, Fossey was found dead in her cabin. Her head and face showed signs of attack by a machete. Theories still swirl around her murder yet to this day, no one has an answer. Though some people suspected robbery, none of her belongings appeared gone. She was buried at Karisoke, right next to Digit.

Legacy

Dian Fossey devoted nearly 20 years of her life to the mountain gorillas and despite the violence done by her and to her, her legacy continues. The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International and the Karisoke Foundation continue to carry on Dian’s work and advocacy. In addition to continuing to protect the mountain gorillas in Rwanda, they expanded their conservation efforts to now protect Grauer’s gorillas in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Macibiri is just one living example of Dian Fossey’s work, dedication and devotion the gorillas.

Dian Fossey is not easy to write about. She challenges us to think about how we honor, or don’t honor, those who broke barriers and did amazing, outsized work, but whose personal behaviors were, at times, abhorrent. We can say, however, that we support efforts of protecting gorillas and the environment they live in, and we support efforts that take into account the needs of people living by these magnificent animals.

References:

- “Update on infant gorilla named for Dian Fossey.” The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International, 12 February 2018. https://gorillafund.org/update-infant-gorilla-named-fossey-fund-kwita-izina/. 09 March 2018.

- “Fossey Fund CEO names infant gorilla at Rwandan ceremony.” The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International, 05 September 2017. https://gorillafund.org/fossey-fund-ceo-names-infant-gorilla-rwandan-ceremony/, 09 March 2018.

- “Dian Fossey Biorgraphy.” The Biography.com website. A&E Television Networks, 27 February 2018, https://www.biography.com/people/dian-fossey-9299545. 09 March 2018.

- Shoumatoff, Alex. “The Fatal Obsession of Dian Fossey.” Vanity Fair. 01 January 1995. https://www.vanityfair.com/style/1986/09/fatal-obsession-198609. 09 March 2018.

- Hogenboom, Melissa. “The woman who gave her life to save the gorillas.” BBC. 26 December 2015. http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20151226-the-woman-who-gave-her-life-to-save-the-gorillas. 09 March 2018.

- Tepper, Fabien. “Why was Dian Fossey killed?” The Christian Science Monitor. 16 January 2014. https://www.csmonitor.com/Technology/Tech-Culture/2014/0116/Why-was-Dian-Fossey-killed. 22 March 2018.

- Osborn, Andrew. “Fossey murder suspect arrested.” The Guardian. 28 July 2001. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2001/jul/28/andrewosborn. 22 March 2018.

Picture Credits:

- Female gorilla - By Wolves201 - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=60454561

- The Dian Fossey Gorilla Fund International (headquarters in Rwanda) - By Azurfrog - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=34335766

- Louis Leakey - By http://www.blm.gov/ca/st/en/fo/barstow/calico.html, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=1979227

- Mount Mikeno - By Cai Tjeenk Willink - Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=15896823

- Dian Fossey’s Tombe - By Zinkiol - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55488160